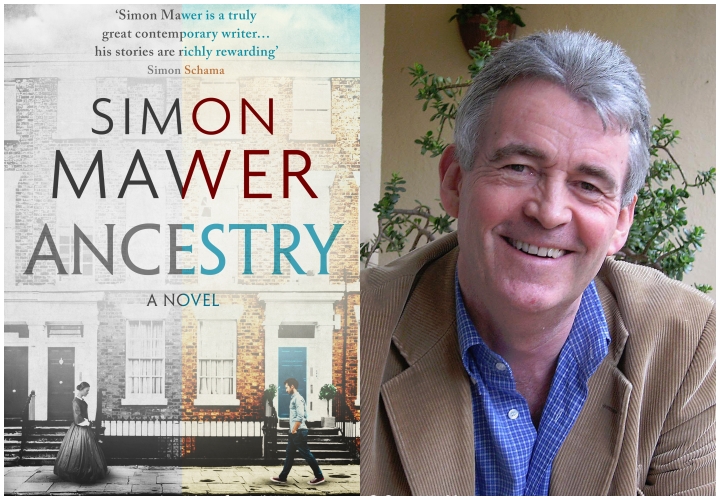

Simon Mawer interview: “these ancestors left no trace beyond the entries in official documents and a single medal from the Crimean War. What were their stories?”

25th May, 2023

Simon Mawer, shortlisted for the third time for the Prize for Ancestry, tells us how family was the inspiration for his novel

I’m delighted to be shortlisted. It is always gratifying to have one’s novels recognised and being shortlisted for a major prize like the Walter Scott is recognition of the highest kind. But for me it will also be an opportunity to meet up again with old friends at the Borders Book Festival and at Bowhill. I’m beginning to feel quite at home there!

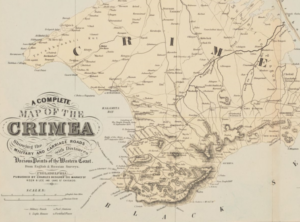

What gripped me was that these ancestors had left no trace beyond the entries in official documents (census entries, birth registrations etc.) and a single medal from the Crimean War; yet they had once existed, every bit as vividly as my great uncle and my grandfather. What were they like? What were their stories? That is what ANCESTRY tries to tell.

Am I a historical novelist? Not in the sense of writing in a particular genre – there are no codpieces or farthingales in my novels – but many aspects of the past do fascinate me, particularly when they bear heavily on the present. For the kind of novels I write, context is important. It is much easier to give context to events and characters if they are set in the past. At least the author knows what is going to happen even if his or her characters don’t.

In the case of ANCESTRY it all started with family. Ever since childhood the history of my family, a very ordinary family, has fascinated me. One great-uncle went ‘over the top’ at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917; his brother-in-law, my grandfather, was in the Royal Naval Air Service and then the RAF. What child wouldn’t be fascinated by the stories they told? But, as an adult, I began to explore the generations previous to them, men and women of whom I had never heard. The genealogy thing. What gripped me was that these ancestors had left no trace beyond the entries in official documents (census entries, birth registrations etc.) and a single medal from the Crimean War; yet they had once existed, every bit as vividly as my great uncle and my grandfather. What were they like? What were their stories? That is what ANCESTRY tries to tell.

In the case of ANCESTRY it all started with family. Ever since childhood the history of my family, a very ordinary family, has fascinated me. One great-uncle went ‘over the top’ at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917; his brother-in-law, my grandfather, was in the Royal Naval Air Service and then the RAF. What child wouldn’t be fascinated by the stories they told? But, as an adult, I began to explore the generations previous to them, men and women of whom I had never heard. The genealogy thing. What gripped me was that these ancestors had left no trace beyond the entries in official documents (census entries, birth registrations etc.) and a single medal from the Crimean War; yet they had once existed, every bit as vividly as my great uncle and my grandfather. What were they like? What were their stories? That is what ANCESTRY tries to tell.

It is much easier to give context to events and characters if they are set in the past

What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts? Answers to both those questions are contained within the novel itself – ANCESTRY is about both the research and that crucial and magical point where fiction grows wings and takes flight from the facts. The facts are the larva and the chrysalis; the fiction is the emergent imago – there’s a biologist’s metaphor for you.

The facts are the larva and the chrysalis; the fiction is the emergent imago – there’s a biologist’s metaphor for you.

In historical writing of any kind there’s a constant tension between the facts and the fictions, but to have any value, the fictions must always express a truth, be it a historian’s interpretation or a novelist’s creation. Such truths may enable wise men and women to interpret the present but I’m afraid just as often historical fictions are mere falsehoods, used to justify morally derelict actions in the present. Perhaps the greatest lesson to be learnt from historical writing of any kind, a truth universally acknowledged, is ‘put not your trust in princes’.