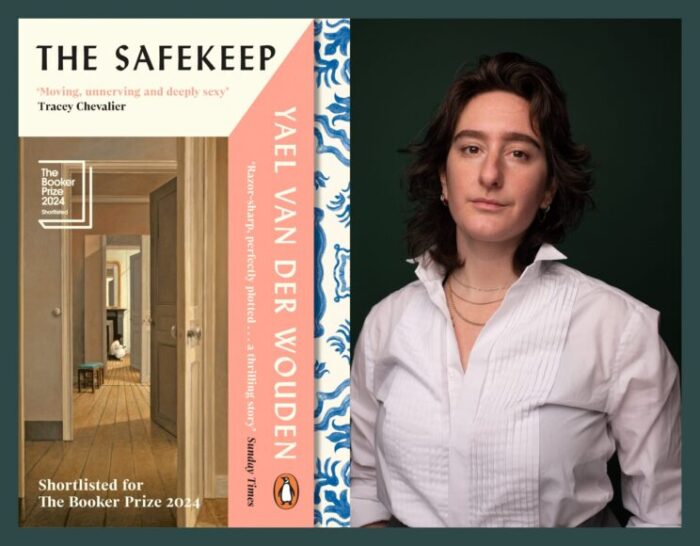

Shortlist spotlight: Yael van der Wouden

1st May, 2025

In the first of our Shortlist Spotlights, Yael van der Wouden answers some of our burning questions about The Safekeep.

Q: How do you feel about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you consider yourself an historical novelist?

A: It’s a huge honour. I have only barely begun to understand myself as a novelist – The Safekeep is my debut! – and for it to be recognised as a worthy historical novel is incredibly humbling. My background is in Memory Studies, where the role of fiction in shaping our understanding of history stands front and centre, so I’m beyond thrilled to be listed among these brilliant historical novelists.

Q: How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

A: Post-war Netherlands is a time and place I’d spent years thinking about, long before I wrote the novel. Growing up Jewish in The Netherlands, the question of what happened to Jewish people after the war is a far more eminent subject for my community than it seems to be for the general public, where the war itself is always central. The question of the fallout of that time, of how to live in the aftermath of brutality, is one I’ve had many conversations about with friends and family. The characters in my novel were born from those talks: a character who is locked in time (Isabel), one who years for modernity (Hendrik), one who’s driven into the future through her anger about the past (Eva) . . . They’re all shaped by that very specific time and place.

Q: What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts?

A: Because of my background in academia and specifically in Memory Studies, research plays a huge (and fun) part in my writing. Both historical research but also through fiction: I pre-empt my writing by reading novels both from the period my novel is set in and novels about that period. My favourite part of the research, though, ends up being the small things: what household items were crucial in the kitchen, for example; what kind of hat was the height of fashion in 1961 Overijssel, and what kinds of clothes were seen as outdated and tacky?

Q: Can writing about the past help us to deal with the present and think about the future?

It must. But first we must realise: history is a narrative, not a truth. Everything we understand about the past has been curated and put together in a certain order to adhere to a certain version of the past that complies with our version of the present. The linearity of history is fiction, man-made; it’s also the only point of access we have. We have to use this human need for narrative at the same time as we must continuously acknowledge its constructed nature and question it. If we point toward the past and say, ‘that bad, we mustn’t repeat it’, and then offer no narrative tools as to how to avoid the bad thing, as to how to recognise a—let’s say, for example—slow decline toward fascism, then we will be doomed to repeat it. Historical fiction can be propaganda as much as it can be a sharply analytical tool. The trick in recognising which is which, is education.