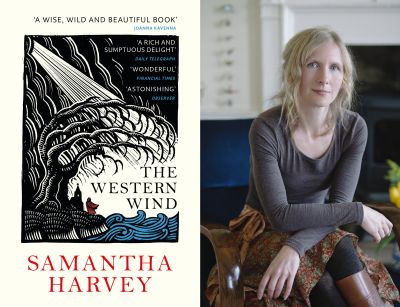

Samantha Harvey – on being shortlisted

6th May, 2019

- What do you think about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you see yourself as a historical novelist?

I think it’s pretty wonderful; I am honoured and elated to be on this shortlist, and to stand among the five other shortlisted authors.

Do I see myself as a historical novelist? No, I would be a fraud to call myself that. This is the first novel I’ve written that has been set historically, and for all I know it could be the last. Each time I begin afresh with a novel I try to do something different in terms of subject, form and style, I try to challenge myself – and that endeavour could take me anywhere in time, place and viewpoint. I never really know where I’m going to go next; I wait to find out. At the moment something very different is brewing, perhaps sci-fi or speculative fiction if only I can think up a good idea.

2. How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

For a long time, and for reasons I can’t quite quantify, I’d been wanting to write a novel that centred on confession and the confession box. I tried to dismiss it as a non-starter – either because too gimmicky or too introspective or not enough opportunity for propulsion and story. But it had, to use your word, lodged in my mind.

Then the bones of a story came – confession as the means by which a priest tries to determine the circumstances around a person’s disappearance. It was only the process of giving that story flesh that my characters came, and my setting in time and place. I had never imagined I’d write anything set in the 15thcentury, I only ended up there by following the trail of the story. Once I was there, everything became both clearer and more opaque – clearer because I knew the territory I was in, and more opaque because I knew nothing aboutthat territory. Nothing. I began with the knowledge of my narrator, a priest, whose voice and essence were immediately alive to me. That, and an illustrated children’s guide to the Middle Ages. And a lot of trepidation.

- What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts?

Here is an example to help answer this question. When I started researching The Western Wind it took all of 15 minutes to discover that there were no confessionals in England in the 1400s – the penitent knelt publicly at the foot of the priest. My story depended upon there being a confessional, so I had three options: I could ignore the facts and have one anyway, I could change the time in which the novel was set, or I could work with the facts and see what opportunities they gave me.

The first option was a non-option; it was too fundamental a fact to ignore and would have emptied all credibility from the novel. The second was also a non-option, for various reasons. The third was the only way, and so I began to look deeper into the practices of late medieval confession, the way churches and parishes were run, the obstacles they faced, and out of that research there grew a rationale as to why thischurch, in this fictional forsaken backwater, might have a rudimentary ‘box’ in the corner, cobbled together out of this and that. And in confecting a rationale for this ‘little dark box’, I suddenly understood so much more about where and what my parish was, who my priest was, what was at stake; my story took on a depth and solidity it hadn’t had before. Research directed fiction which necessitated more research which gave life to more fiction.

The two are so dynamically linked. Research is a rich, rich source of creativity. You need to know what is true about your subject in order to know what you can legitimately make up. And when you are making things up, you need to be able to answer a confident yes to the question: could this conceivably be true?

- Do you think that writing about past events is important for society?

‘Important’ is a difficult word. Important for who, for what? And do books – in our case novels – need to be important? I honestly don’t know.

For myself, I like writing that sees its subject matter with a truthful clarity, and I do think that truthful clarity is important when we’re looking at anything, including the past. If writing about the past can bring context, or overturn magical or mythical thinking, it can help us navigate our present and envisage our future.

Take J.G. Farrell’s The Siege of Krishnapur as an example of a brilliant, boisterous (yes, boisterous) novel about the Indian War of Independence in 1857. But it’s also an unsparing piece of writing about colonialism and Victorian mores, about the idiocy and cruelty that are the logical consequences of pomposity and unchallenged power, about the dangers of entrenched nationalistic thinking, and about how sad, how tragic it is when we refuse to be flexible in our views. Is it socially important to have writing like that? Maybe, yes – but its first responsibility as a novel is to be brilliant, I think, rather than to be important.