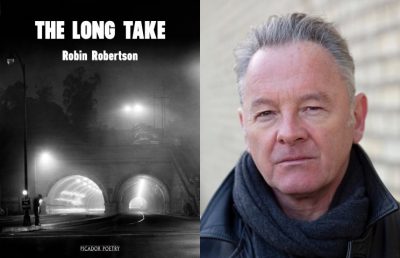

Robin Robertson – on being shortlisted

9th May, 2019

In the final post in the series, Robin Robertson gives us a fascinating insight into the writing of his shortlisted book The Long Take.

- What do you think about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you see yourself as a historical novelist?

It’s a great honour and a delightful surprise – particularly given that The Long Take is, formally, something of a hybrid. If you’d told me a year ago that it might reach the shortlist for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction I would have been astonished, but the book is certainly a fiction and is absolutely set in the historical past.

Beyond that, the genres start to shift a little. The book’s nature is restless and mutable, because I was attempting to combine the propulsion of long-form narrative with the lyrical intensity of poetry. As I began to write, I saw there were rather filmic ways of interleaving the narrative present – with flashbacks, particularly, but also by creating a montage of storyline, dialogue, memories,diary entries, postcards and photographs: always intercutting poetry and prose.

Perhaps as a result I’m rather resistant to most labels, really, but happy to be called a writer.

- How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

I wanted to write about cities – particularly being an outsider in a foreign city, because that was how I felt moving from Aberdeen to London in the late 70s. London is now over-familiar to me, so setting the book in the US, in the historical past, offered me distance and perspective. It also allowed for a central character, Walker, who was North American but not American: a young man who had suffered great hardship, who came from a rural background in a neighbouring country to the north; someone brought up on the same land-mass, with the same language, but who was now an outsider, an alien.

The tone, and some of the techniques and imagery, derive from film. I was very taken by American post-war black-and-whites with titles like Out of the Past, Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Heat, but it was only when I moved down south that they properly made sense. What interested me originally was the existential dread in these films – that sense of being ‘the other’. Suddenly, I felt everything I was experiencing in those first years in London was being matched in those films: excitement, disorientation, vulnerability, loneliness, desire, terror, loss… And then I found out they had a name – film noir – and that they had emerged directly from history: made in America by émigré directors and cinematographers who had fled Nazi Germany, bringing with them all their skills, all their sensibilities and terrors. It was a style, a ‘way of seeing’, that had clear socio-political origins. These post-war years in the USA seem to me to be absolutely pivotal: they delivered the best jazz and best films to a country that now led the free world; but it was also the decade where the American Dream soured and the long slide began.

- What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts?

I always try to write out of experience, or at least out of an experience in landscape, so I did my geographical research in Inverness County, Nova Scotia, and walking, over many years, the streets of Manhattan, Los Angeles and San Francisco. This book also required a significant amount of more conventional research, in areas where I knew little – American civic planning, for instance, or the war history of the North Nova Scotia Highlanders – and I also watched and re-watched over 400 films.

The Long Take is peppered with real historical events – for a sense of verisimilitude, to reinforce the timeline, to point up some important contemporary social and political moments, but also to remind us of certain facts: that lynching continued into the late 50s, early 60s, say, or that paranoia about Russian infiltration is nothing new.

My hope was that this geographical and historical accuracy would allow the reader to trust the emotional terrain.

The research took a couple of years to be assimilated, then I took away all the scaffolding and wrote for another two years without consulting my notes. I knew what Walker was escaping from, and which cities he would spend time in, but almost nothing beyond that. I just dropped him on the banks of the Hudson overlooking Manhattan and let him go.

- Do you think that writing about past events is important for society?

The older I get, the more certain I am that this is true. We are currently living in accelerated times: of both instant information, often superficial and inaccurate, and wholesale amnesia. As Santayana famously said, ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ One of the things I wanted to point out in my book is that the seeds of the current catastrophe in America – political greed, hypocrisy and corruption, inner-city collapse, social divisions beyond the already-institutionalised racism, and a right-leaning ideology that encourages insularity, paranoia and fear and hatred of the outsider – were sown in 40s and 50s.