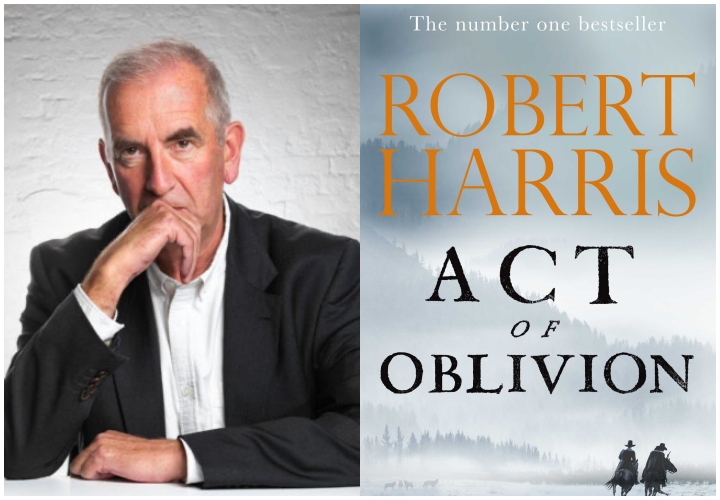

Robert Harris interview: “A 17th century manhunt. I thought: what if I invent a character who co-ordinated the search?”

18th May, 2023

Robert Harris, shortlisted for the third time for the Prize, tells us what inspired him to write Act of Oblivion.

Obviously, I’m very flattered to be shortlisted for the third time. It’s the biggest prize in the world for historical fiction. The first time, for Lustrum, I lost to Hilary Mantel (no disgrace in that!); and the second time, for An Officer and a Spy, I won. It’s an honour just to be in the company of such fine writers. I think of myself essentially as a novelist – a political novelist, if anything, as almost all my books are about power and people caught up in the drama of political ambition.

The hunt for the signatories of Charles I’s death warrant started when the royalists returned to power in 1660. It struck me as a wonderful concept – a 17th century manhunt – and I thought: what if I invent a character who co-ordinated the search?

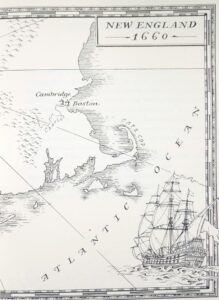

I read a tweet referring to “the greatest manhunt of the 17th century”. That intrigued me, so I clicked on the link and it took me of the story of the hunt for the signatories of Charles I’s death warrant that started when the royalists returned to power in 1660. It struck me as a wonderful concept – a 17th century manhunt – and I thought: what if I

invent a character who co-ordinated the search? Then, when I researched further, I realised that the characters of Colonel Whalley and Colonel Goffe, father- and son-in-law, fleeing across Puritan New England, would enable me also to write about the early days of the English settlers in America.

invent a character who co-ordinated the search? Then, when I researched further, I realised that the characters of Colonel Whalley and Colonel Goffe, father- and son-in-law, fleeing across Puritan New England, would enable me also to write about the early days of the English settlers in America.

Research is all-important, and takes roughly as long as the actual writing. In many ways it’s the most creative part of the process, when characters start to form in my mind. I’ve never employed a researcher: you never know what tiny detail will trigger your imagination. For me it’s the equivalent of the lived life, when I immerse myself in my chosen period and its people. I generally know about ten times more than I’ll ever use. And then it’s very important to forget it all, and just tell the story, using only those facts that are relevant.

Act of Oblivion was published in the week that the Queen died and I was startled by how many of the arguments that went on about the virtues of a monarchy versus a republic nearly 400 years ago are still relevant today.

Can writing about the past help us to deal with the present and think about the future? This is one of the great justifications of historical fiction. It reminds us that basically human beings don’t change, that they face the same moral dilemmas that we do, that politics just goes round and round. Act of Oblivion was published in the week that the Queen died and I was startled by how many of the arguments that went on about the virtues of a monarchy versus a republic nearly 400 years ago are still relevant today.