Peter Carey – on being shortlisted

2nd May, 2019

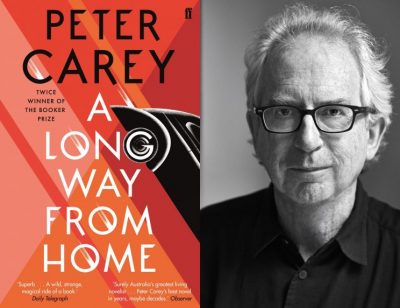

The Prize is honoured to publish a series of exclusive Q&As revealing the inner thoughts and inspirations of the 2019 shortlisted authors. First in our series is Australian author Peter Carey, shortlisted for A Long Way from Home.

- Do you see yourself as a historical novelist?

Given the dirty secret (that I want to win the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction) it would, surely, be insane to say anything but “yes”. After all, I have written nine novels that could be reasonably described as historical fiction. I am at work on another one right now.

Even so, I feel compelled to insist that my primary engagement is not with the past but with our present terrifying age and the volcanic forces that have made me who I am, that is, an Australian, a creature of the long ago British Empire. I am a modern writer. I am colonial at my core, the progeny of Magwitch and that Victorian anxiety of “the convict stain”. I am a descendant of James Joyce and William Faulkner. I live in the Anthropocene Age. I am a citizen of modern Australia whose loudly independent citizens cannot yet vote for a Republic.

Past, present, future, these are the tectonic forces that shape my fiction.

- How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

I was twelve years old. I was part of a small crowd in the main street of Bacchus Marsh in the middle of the night. One moment all was quiet and then Redex Trial cars roared through our town on the way to the finish line. The whole country had waited for them, these survivors of a 16,000 mile journey over roads that could break a chassis clean in half. There was no TV on which to watch the adventure, but there were newsreels and newspapers following their every mile. Now here they were, in real life, roaring down Stamford hill, past the doctor’s, and the blacksmiths, battered, broken, covered with mud and decals advertising spark plugs and motor oil. It was a magical moment worthy of Fellini’s Amacord.

Sixty years later I saw the same cars , preserved on YouTube, careening across the Top End of Australia. This time I noticed that there was not an aboriginal seen or mentioned, not a clue that these white maniacs were crossing Aboriginal territory, inevitably blind to mythology, ceremony, the storylines that had webbed the continent for 60,000 years. The drivers had strip maps, white fellah maps, showing where the creeks crossed the roads, they were travelling blind to sacred ground. They could have driven up the aisle of a cathedral and never known.

This was where I saw my novel: two maps which could only exist in 1954. There were, as yet, no characters, no proper story just those maps, two cultures, within one could encompass empire, invasion, and the delicacy of an ancient civilization. Moments like this don’t come often in a writer’s life and I recognised it straight away. In the year of 1954 there was a lens for seeing the twenty-first century, land rights, stolen children, the pain of alienation, but also a conduit for sunlight, humour, love, everything which makes the darkness bearable.

- What place does research have in your writing?

I always like those times when the requirements of real life get in the way of fiction, the moments when an expert source insists that what I’m imagining is impossible. This happens in libraries, of course, but I love conscripting real live experts to imagine how my impossible thing might somehow happen. Time and time again these encounters lift the story to a higher plane I could never have climbed to on my own.

If I have a Greek Australian character I’ll give a draft to a Greek Australian to read. And in the case of A Long Way from Home I collaborated with many experts, including the Aboriginal readers who sometimes wrote my dialogue for me, and taught me what I should have known, for instance that Aboriginal has a capital A just like Australian.

- Do you think that writing about past events is important for society?

As Faulkner wrote: “The Past is not dead. It is not even past.”