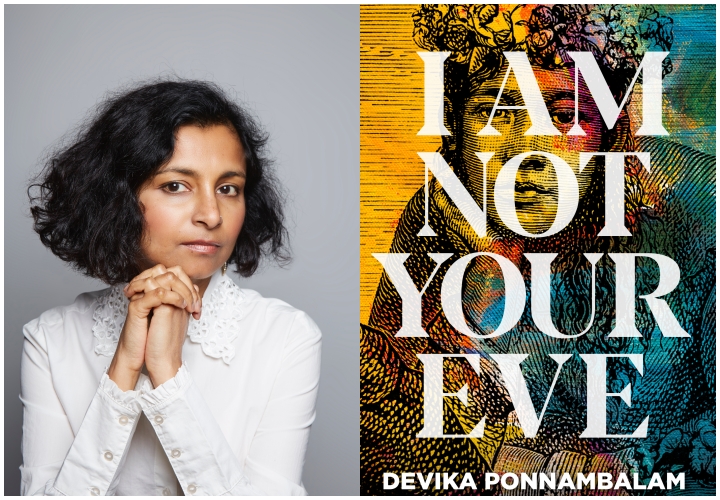

Devika Ponnambalam interview: I wanted to write my way into a part of the past that seemed unjust, and unfinished somehow

13th June, 2023

Devika Ponnambalam, whose book I Am Not Your Eve gives Paul Gauguin’s muse and child bride Teha’amana a voice, tells us how she feels about being shortlisted

I am beyond thrilled to make it through to the shortlist! The profile of the award will bring Teha’amana’s story to a much wider readership, which is truly wonderful. I felt so passionate about telling her story that it took me seventeen years to write – I began writing it in 2003! Strangely, I never thought of it as an historical novel. It felt like I was writing something that didn’t fit into any kind of genre. I just wanted to write my way into a part of the past that seemed unjust, and unfinished somehow. I wanted to give a voice to this indigenous girl who had effectively been written out of history, silenced, and yet her image is worth millions today.

I had read a magazine article about Paul Gauguin a few years before I began working on the idea. It was about the painter, his tormented life, and his journey to the South Seas, and there was the image of one of his paintings, The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch, embedded within the article. In it, Teha’amana, his model, muse, first Tahitian lover, and child-wife, is looking out towards the viewer. It is such a powerful image and struck a deep chord with me. I was hypnotised, transposed to that world. I wondered what had happened to her because the article also said, very ‘off-the-cuff’, that Gauguin had later died of syphilis.

I had read a magazine article about Paul Gauguin a few years before I began working on the idea. It was about the painter, his tormented life, and his journey to the South Seas, and there was the image of one of his paintings, The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch, embedded within the article. In it, Teha’amana, his model, muse, first Tahitian lover, and child-wife, is looking out towards the viewer. It is such a powerful image and struck a deep chord with me. I was hypnotised, transposed to that world. I wondered what had happened to her because the article also said, very ‘off-the-cuff’, that Gauguin had later died of syphilis.

I loved the myths and legends I read. I wanted them to find a way into my story, to show what had been lost and to honour the Polynesian culture and its oral tradition.

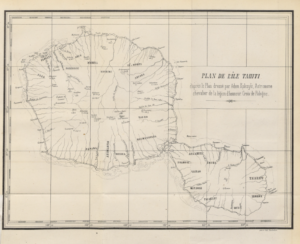

In the beginning, I did a lot of research in the British Library in London, and then, in 2018, I went to Tahiti, and that was the turning point for me. I had relocated to Edinburgh in order to finish writing the book and secured a travel and research grant from Creative Scotland. I was dealing with a story set more than one hundred years ago, in another hemisphere, in a culture very different from mine. One that had been damaged by Western contact and all the questions that entailed. I found the academic research, missionary accounts and anthropological studies, to be dry and uninspiring, but I loved the myths and legends I read. I wanted them to find a way into my story, to show what had been lost and to honour the Polynesian culture and its oral tradition. As a filmmaker, I prefer looking at images and paintings and dreaming my way into them. Gauguin’s paintings represented the first doorway into that world for me – because of how visceral his Art is. I wanted to tell a simple human story, one about a girl, her innocence, her betrayal, and her awakening. Even when I went to Tahiti, I found that her story was still missing.

Writing the past sits between truth and fiction, because the real story, the story that exists in the main character’s head is never really yours.

I wrote about something that happened in the past in order to process what happened, for myself. Hopefully I’ve taken readers on that journey too. It has been a difficult one. Writing about the past definitely informs the present; it opens up debate, and in this case, old wounds, and generational trauma. It is about challenging what went on before, what was accepted truth, and moving forward with a new version of it. Writing the past sits between truth and fiction, because the real story, the story that exists in the main character’s head is never really yours, so you have to do the unearthing, and put something of yourself there.