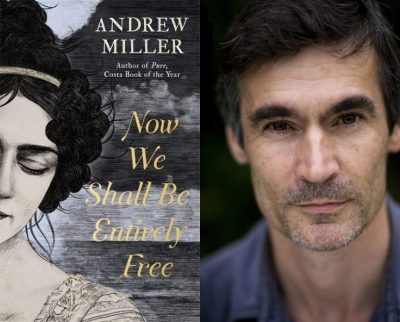

Andrew Miller – on being shortlisted

7th May, 2019

Andrew Miller, author of Now We Shall Be Entirely Free, gives us his thoughts on being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize.

1. What do you think about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you see yourself as a historical novelist?

I am very happy to be noticed by the Walter Scott! I think over the last ten years it’s established itself as a serious prize for serious work. And I remember how enjoyable it was the last time I was shortlisted with Pure. Do I see myself as a historical novelist? No, not really. Perhaps not even as a novelist. Just a writer, one who works with particular forms – but next time…

2. How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

The book had its origins in music, specifically a little piece called Mary Young and Fair, which (according to the music manuscript page I had) was collected by a military type in the Hebrides in 1815. But I have had a slight obsession with the period since boyhood.

3. What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts?

Research to me is a word with a slightly dead ring to it. I do something closer to beach combing. I drift in and out of the available material, pick up whatever looks helpful, whatever lends itself to the project, whatever lets me see more clearly. I like to get things right, to be accurate as far as I can. But I treat everything as freely as necessary. Everything is at the service of the story, though as I find things out so the story shifts. In research I learn about the possibilities and restrictions of any given situation or time. So it’s a to and fro.

4. Do you think that writing about past events is important for society?

Henry Ford (I think) said ‘History is bunk!’ I like that. Hilary Mantel, a little more recently, said history is what’s left in the sieve when the centuries have poured through. I like that too. For me, there’s no sense of separation between the ‘what was’ and the ‘now’. All of it is hopelessly tangled together, as it is in our individual lives. I may have, for reasons I don’t understand, a kind of heightened sensitivity to what – in terms of time – is out of view, or mostly so. I love the suggestiveness of an old letter or an old house. A flight of stairs with the stones worn away by countless feet going up and down, that always moves me, excites me. Is it important to write about the past? I think the obvious answer to that must be yes. Or, to put it another way, to try to avoid the past because of some idea that it’s done with and without relevance would be to condemn yourself to a kind of amnesia, to be wilfully ignorant. Why do that? I think it’s important to add, however, that setting a novel in the early Nineteenth Century does not make it a Nineteenth Century novel. I have no interest in that, in pastiche. Whatever is written today belongs to today and its value as literature depends on its ability to ‘sound’ in the present. The past – even the rigorous past of academic historians – is the past held in the belly of now. This is a paradox. What it doesn’t mean is that everything is subjective, merely a matter of subjective interpretation. What it does mean (perhaps?) is something akin to those lines in Elliot at the beginning of Burnt Norton.