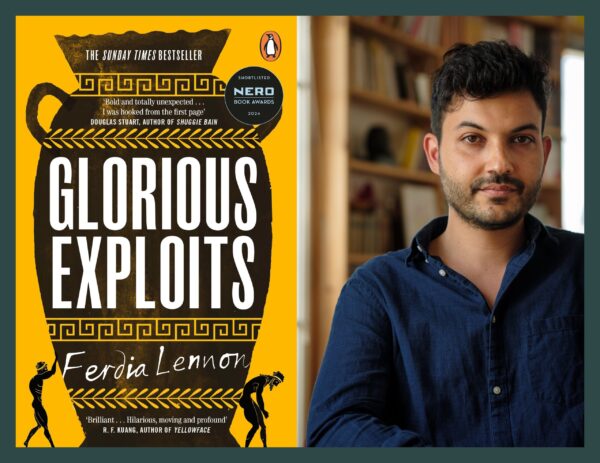

Shortlist Spotlight: Ferdia Lennon

15th May, 2025

Ferdia Lennon, shortlisted for Glorious Exploits, answers our questions.

Q: How do you feel about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you consider yourself an historical novelist?

I feel incredibly honoured. Many of my favourite novels of the past twenty years have been shortlisted for the prize, and my all-time favourite historical novel, Wolf Hall, won the inaugural award. As a historical novelist—which I very much consider myself to be—it’s simply wonderful.

Q: How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

As a child, I stumbled upon a book about Greek mythology and was instantly captivated; the gods, heroes, and epic tales became my special topic. I’d even have my brothers—and anyone who’d oblige—quiz me on it all. Then, as a teenager, I read Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, and, for reasons I still can’t fully explain, something clicked. I became completely obsessed—with the book and with 5th-century BCE Athens; this complex society, in many ways so alien to our own, yet rendered with such relatable immediacy that it felt impossible to believe the mind that conjured it was no longer living, much less that it hadn’t done so for thousands of years.

Q: What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts?

I feel research is the foundation of good historical fiction. If you’re not genuinely interested in the history—the real context and worldview of the period you’re writing about—then why not just write fantasy or speculative fiction? That said, it’s crucial to let the research serve your story, not the other way around. There’s nothing in Glorious Exploits that contradicts the historical record, and yet the novel is very much built in the gaps of that record. It’s a work of fiction which occupies the space of what we don’t know, grounded in what we do.

Q: Can writing about the past help us to deal with the present and think about the future?

Absolutely. Barry Unsworth, the great historical novelist, described historical fiction as a distant mirror in which a writer could use the specificities of the past to say something about our present. Even Thucydides saw his History of the Peloponnesian War not just as a record of a local conflict but as a template for understanding recurring patterns in human behaviour and the roots of conflict, which would be relevant for generations to come. I think the best historical fiction harnesses history’s ability to reveal something essential about human nature—and, in looking back, tells us something about ourselves in the here and now.