Cressida Connolly – on being shortlisted

3rd May, 2019

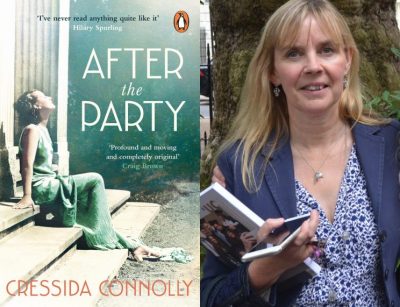

The second in our series of Q&As is from Cressida Connolly, author of the shortlisted novel After the Party.

- What do you think about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you see yourself as a historical novelist?

I thought: “Oh, lucky me! What a delightful thing to have happened.” I also felt really proud to be among such fantastic company because I so much admire the other writers on the shortlist.

The fact that it’s a prize for historical fiction is especially pleasing, to me, because I see history as the most important source of information we have: more than any library, more than internet search engines – the past can inform us and help us to see ourselves more clearly. It can also tell us the most wonderful stories.

I see myself as a novelist whose work implicitly draws parallels between the past and the present. After the Party is set during the late 1930s, a time of enormous political upheaval throughout Europe. It’s about someone who, almost unwittingly, finds herself being drawn to the political Right; something that’s occurring in our times, too.

2. How did the people and times you write about in this novel first lodge in your imagination?

A book of photographs of Sir Oswald Mosley’s British summer camps from the 1930s fell into my hands and I got that tingly feeling, of knowing that I’d have to write about them. It shows holiday makers by the sea in sunny Sussex, swimming and putting up tents and larking about. But then, when Mosley appears, these same people all stand and give the fascist salute. I peered and peered at their faces, trying to find traces of wickedness, I suppose; but they just looked like ordinary people. I thought it would be fascinating to see how they got there, psychologically and ideologically.

3. What place does research have in your writing? When does the fiction take over from the facts?

Research is vital. It’s the scaffold that fiction is built from. If you’re a nosy bookworm – and I am – it’s also tremendous fun. I love burrowing in old archives and libraries, there’s always the feeling that I might stumble upon some wonderful source from which characters and story can develop. The fiction takes over during the actual writing process.

4. Do you think that writing about past events is important for society?

Yes, very much so. Our past is our collective heritage, our collective memory. It’s something we can all share and be enriched by and learn from. Most importantly, the past can deepen our awareness of how we all are connected to one another. There’s an extraordinary moment in a documentary film of Werner Herzog’s, about the pre-historic cave paintings in France: when he’s interviewing an archeologist about the people who made the paintings, he asks him whether these people cried in the night. And of course the scientist cannot answer that, because there is no evidence that they did. But what Herzog was driving at, I think, is that they were people, just like us. They loved and suffered, exactly as we do.