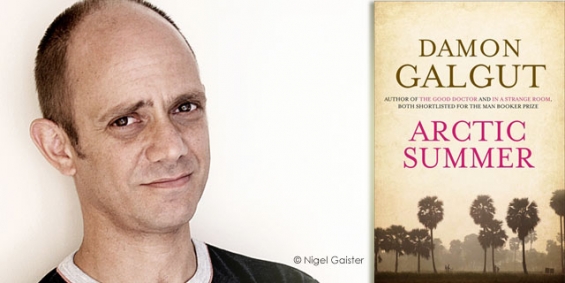

Author spotlight: Damon Galgut

12th June, 2015

Damon Galgut, shortlisted for Arctic Summer, answers some questions about his writing and being shortlisted for the Prize.

What do you think about being shortlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction? Do you see yourself as a historical novelist?

I’m delighted to be on this shortlist, although I have never aspired to being an historical novelist. The history was a means to reach the subject of real interest – namely E.M. Forster and his struggle to write A Passage To India. If that struggle didn’t feel, in a vital way, absolutely contemporary, it wouldn’t have interested me. The old-fashioned notion of historical fiction as a kind of colourful pageant, full of carriages and cannons and sails, just doesn’t excite me, either as a reader or a writer.

Why did you choose real people and events to write about in this novel? Do you have a personal connection with E.M Forster?

I’ve been wanting, for a while now, to write a novel about writing a novel. Forster’s story was of special interest because of the fight with himself to get his novel done. The whole process took 11 years, and he was stuck for 9 of them – nine years in which he fell in love, lost his virginity, retreated to Egypt for the duration of the First World War and worked in India as Private Secretary to an eccentric prince…What writer wouldn’t be stirred by a canvas that’s so epic and intimate at the same time? I have always admired Forster’s work, but I suppose my connection is less with him than with India, a country I have visited 12 times now.

How do the people and times you write about first lodge in your imagination?

Usually a book begins with the sense of a few people caught in a situation that has the potential to unfold in different directions. In the case of this book, I was especially drawn to Forster’s relationship with his friend Masood, to whom A Passage to India is dedicated. It became increasingly clear how that novel grew out of Forster’s unrequited love for his friend. Tracing the arc of their relationship was inseparable from the story of how Forster’s book came to be written. At the core of all the surrounding history, that is the knot I wanted to unpick.

At which point do you let fiction take over from research?

Normally research is a minimal part of what I do. But in this case, I spent a full year reading before starting to work. It was important to me that I get the facts right. When I began to imagine how things might have been, and what particular people might have said to each other, I wanted to be speculating in a realistically possible way. To put it differently, I wanted to tell the story of what might indeed actually have happened, not to invent freely for purposes of ‘entertainment’. I have let my imagination loose, of course, but always with fidelity to what is known about the times and people concerned. You might say that the established facts are the skeleton of the book, while what’s invented is the living tissue on the bones.